Article by Debra Freeman

Photography by Fitz

Lead Photo: Freeman with a Congo watermelon in Delaware

I was at work a few years ago when I came back from lunch and ran into my boss who was standing outside my office door with a worried and hesitant look on his face.

“Hey, what’s up?” I asked. “So, Deb…I need you to stay calm,” he said. “What’s wrong? What happened?” I asked anxiously. “Uh…there’s a watermelon on your desk,” he said sheepishly. I paused and blinked a couple of times. “A what?” I asked. “A watermelon,” he said quietly. Cue uncomfortable pause. “There’s… a…watermelon?” I asked again. “Yeah. John brought it by for you,“ he said, and walked away.

I walked into my office and shut the door. I expected to see a bowl of cut watermelon on my desk. Instead, there was a small, uncut watermelon sitting there. I was taken aback and stood dumbfounded. I struggled to process what was happening. Was this just a friendly gesture? Was it just assumed that I would be excited to take a watermelon home because I was black? I must’ve stood frozen in place for about five minutes before I threw it in the trash.

I’ve eaten watermelon in the privacy of my own home many times. Never in public. As a black American, I am painfully aware of the stereotypes associated with them. In fact, my mother collected black memorabilia, so I can remember seeing vintage lithographs and advertisements throughout the house of brown faces drawn grotesquely while holding slices of “nigger apples.”

Although I wasn’t explicitly told not to eat watermelon in public, it seemed to be an unspoken rule.

Fast forward to a few months ago, where I read about the Bradford watermelon on Facebook. The Bradford watermelon was thought to be extinct and was considered one of the sweetest watermelons. These watermelons are hard to find because they aren’t sold in stores. The rind is too soft and cannot be shipped without danger of breaking. However, I was able to purchase one from the Bradford farm online for $20 and was fully prepared to wait until August to travel to Sumter, South Carolina. I figured it would be a fun road trip with Fitz and I was excited to eat an heirloom fruit from the 1800s that most people had never tasted. Other than that, I didn’t think that deeply about it.

Shortly after ordering it, Fitz started researching different types of heirloom watermelons. I came home every day to hear about different types and each day, it seemed, there was yet another one that was rare. They had names like Orangeglo, Moon and Stars, and Cream of Saskatchewan. Soon, we were getting up early on Saturday mornings and tracking down farmers to see what types of melons they grew, and one weekend we found ourselves at a farmers’ market in Asheville, North Carolina. We were able to identify a Sugar Doll and a Jubilee on sight and high fived each other, pleased with our burgeoning knowledge.

We had impromptu photo shoots with the melons, and I ate each one. In the privacy of my kitchen.

We’ve driven more miles than anyone would’ve guessed. Fitz and I have gone to Maryland for a Georgia Rattlesnake, to Delaware for an Ali Baba, to rural Virginia to visit the Southern Exposure Seed Exchange where we found a Missouri Heirloom and a Yeni Dunya, and to Pennsylvania for an Ancient Crookneck.

Freeman and Fitz filming with an Ali Baba watermelon brought back from Delaware

We found watermelons with red flesh, yellow flesh (affectionately called “yellow-meat” in some parts of the south) and we’ve realized there were watermelons with orange and white flesh as well. Farmers’ markets weren’t enough anymore. Fitz started driving to actual farms to hunt down obscure watermelons, and Dr. Howard Conyers, pitmaster and rocket scientist, told me about the Odell’s White.

Through some deep rabbit hole research, Fitz was able to find one at Crumptown Farms in Farmville, Virginia. Farmer Brad Constable, who grew the Odell’s White, noted that when cut, the inside of the stem was red. Like blood.

The sappy red stem of an Odell’s White heirloom watermelon

Watermelons originated in West Africa. I immediately thought about how many of my ancestors must have hidden seeds in their hair and ears during the middle passage to bring some small part of their home with them to an unknown land. A land that would shame them, work them to death and whip their bodies mercilessly while reveling in the very skills and ingenuity they were prized for.

According to David Shields, Carolina Distinguished Professor at the University of South Carolina, Chair of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation and Head of the Slow Food Ark of Taste for the South, the Odell’s White is the only known commercial variety of watermelon grown by an African American. His name was Harry (like many that were enslaved, he doesn’t have a last name) and he was the foreman of pomologist William Summer in Pomaria, South Carolina in the 1840s. The Odell’s White was thought to have been lost in history but was discovered to have been misnamed as the Stoney Mountain Watermelon. This watermelon is a difficult one to track down – it grows up to 60 pounds and isn’t widely sold.

As I tried to find out more about Harry, I learned more about where the watermelon stereotype came from and was surprised to discover that newly freed slaves sold watermelons to support their families during reconstruction. Not only was it a way to earn money, but I imagine it was a point of pride to be paid for their work. This newfound sense of equality threatened the racial “balance” in the south. Soon postcards, newspaper images, songs, and scenes in movies featuring black people that wanted to eat watermelons all day popped up to remove any sense of humanity while creating images of laziness.

This entire time I was ashamed of something I needed to be proud of. People who lived hundreds of years ago and who looked like me were entrepreneurs, seedsmen and women, and farmers. These people were not the figures from my childhood that were granted no humanity.

The time had come to drive to South Carolina. As we drove for six hours in the early moments of the day, I thought about those who had come before me. Those unknown and lost forever. The ancestors that I share my DNA with but would never know. After all, they were listed in tax records as property, not by their names. The farther south we traveled, the more I realized that I wanted to reclaim some of that lost dignity for them, although I wasn’t even sure if that was possible.

Meeting with Nat Bradford at the Bradford Watermelon Company Farm

We were able to meet with Nat Bradford, who was generous with his time and knowledge about any and everything related to the Bradford watermelon. While standing on the Bradford farm in the pouring rain under a tent, I ate my first slice of watermelon in public. And I was the only black person there.

It’s a heavy mantle to wear at times. To carry the burdens of those who came before. To be a personified stereotype for those who are ignorant. I’d like to tie this experience into a tidy bow. I’d like to think I won’t feel self-conscious if I eat a slice in public – it’s happened once after all, so it can happen again. Realistically though, I probably will pause before deciding. But at least I’ve allowed myself to have a choice.

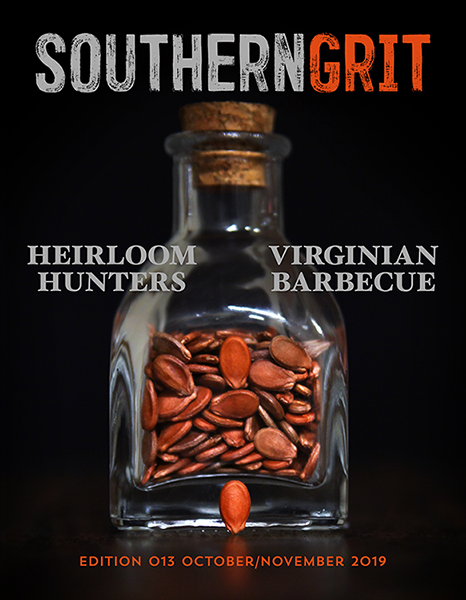

Article originally featured in the 013 print edition of Southern Grit Magazine.

To order your copy visit HERE or click the image below

4 Comments

Just clicked over to this article from one in the Virginia Pilot shared on Facebook. This is a wonderful article about the history of heritage watermelons, written by a lady of candor and pride and self-awareness who also happens to be black. So appropriate in these turbulent times (I wrote this note on 8-25-2020, during surely one of the most messed up political times in US history). Thank you for sharing it.

How can I get in touch with u

?

Love to have 10 of them. Thanks

As long as there seeded watermelons ! Old fashioned is the best ! I do not like the chemical taste in the seedless watermelons.