Boat commander. Abolitionist. Former slave. This is the story of Moses Grandy.

Article by Debra Freeman | Graphic illustration by Kyle Melendez and Elena Bundy

Born in Camden County, North Carolina around 1786, Moses Grandy was born into some of the most inhumane conditions possible. When he was a small boy, his mother hid him and his eight siblings in the woods to prevent their master, Billy Grandy, from selling them. Grandy promised not to sell her children if she returned; he shortly sold them all, except Moses. When Moses’ mother protested, she was whipped as punishment.

Moses often played with his master’s son, James Grandy, as they were around the same age. Billy Grandy willed Moses to James upon his death, and James inherited Moses around 1794. As was the custom of the time, while James was young, Moses was hired out annually to various owners until he and James were twenty one years old. His playmate was now his owner.

At age 10, he was hired out to Jemmy Coates, who often beat him. His next owner, Enoch Sawyer, did not feed him, and Grandy wound up grinding corn husks to make flour for food. When he was 15, he began what would become his life’s work by working on the water. His initial job was to be in charge of ferry crossings at Sawyer’s Ferry, and most nights to keep warm he would place his feet in the mud where pigs slept.

Grandy also transported a variety of goods to Portsmouth and Norfolk along with cutting timber for the creation of the Great Dismal Swamp Canal, which was difficult work. The creation of the Great Dismal Swamp Canal created a much needed shipping route between inland areas of North Carolina, Portsmouth and Norfolk. Grandy describes the working conditions as follows, “The ground is often very boggy: the negroes are up to the middle [of their bodies] or much deeper in mud and water, cutting away roots and bailing out mud: if they can keep their heads above water, they work on. They lodge in huts, or as they are called camps, made of shingles or boards. They lie down in the mud which has adhered to them, making a great fire to dry themselves, and keep off the cold. No bedding whatever is allowed them; it is only by work done over his task, that any of them can get a blanket. They are paid nothing except for this overwork.”

———————————————————————————————————–

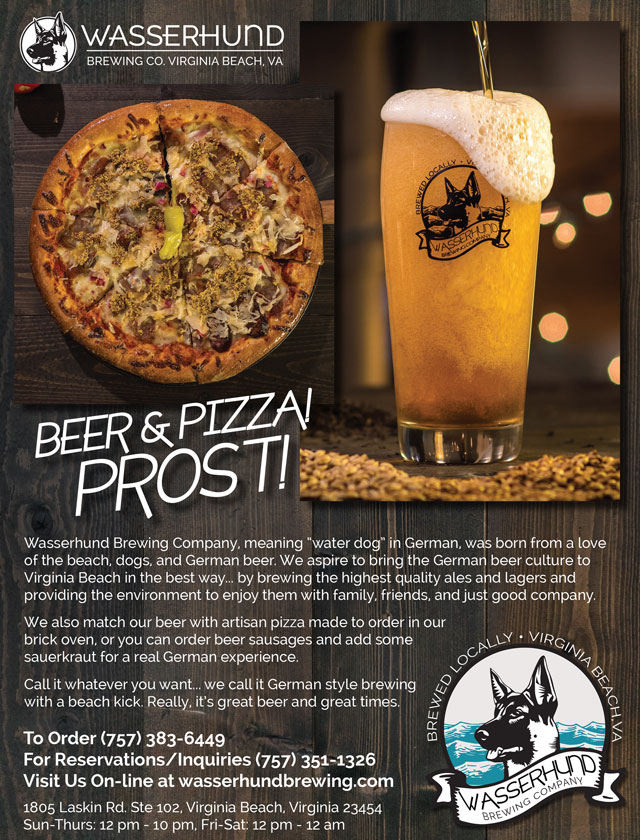

For more on Wasserhund’s German style beer with a Beach KICK, visit them online at wasserhundbrewing.com or click the flier above.

———————————————————————————————————–

Through his work on the water, he learned navigational skills and became known to have a talent for managing boats. In 1813, he was hired out to his master’s brother-in-law, Charles Grice, as a freightboat captain. Eventually Grandy became the captain of four vessels that ran along the Great Dismal Swamp Canal and the Pasquotank River, which was the only water passage between Elizabeth City, North Carolina and Norfolk when the British blocked the Chesapeake Bay during the War of 1812, which lasted until 1815. Because of his skill, he was now paid a wage based on the value of what he was transporting.

During this time, Grandy met and married the woman that he loved, “as I loved my life.” Unfortunately, he was not destined to be with his wife for long; while at work on the river, he saw his wife chained to a group of other slaves walking to a boat which was likely headed south. They were only married for eight months. Grandy would never see her again.

After this devastating loss, Grandy resolved to try to purchase his freedom. He made payments totaling $600 to James Grandy, and when the final payment was made, instead of signing papers to free Moses, James instead tore up the receipts that would indicate full payment for Moses’ freedom, and went to the local tavern for a drink. Shortly afterwards, he sold Moses to another slave owner, while pocketing the money for himself.

Grandy’s new owner, a man named Trewitt, allowed him to be hired out, and although Grandy earned money for his work, he had to pay a portion to Trewitt. Miraculously, Grandy once again saved $600 to purchase his freedom. Trewitt accepted Grandy’s money, yet did not free him. Grandy became depressed and refused to work. In response, Trewitt threatened to sell him, and Grandy responded by saying he would “cut his throat from ear to ear rather than go with him.” Trewitt changed his mind, presumably after recognizing this was a fiscally unwise decision.

Shortly afterwards, Grandy was again sold to Edward Minner, who bought him for $650, and was once again told that he would be able to purchase his freedom. After three years, he earned his freedom, and Grandy “was althoughter on the footing of a free man, as far as a colored man can there be free.”

————————————————–

To begin your culinary journey visit chefva.com or click the flier above.

————————————————–

After finally being granted his freedom, Grandy worked on boats in the north that shuttled between New York and Philadelphia, but made the painful decision to move back to North Carolina in order to work to purchase his family. However, when Minner died, Grandy moved back to the north. Being a free man in the south without a former master to vouch for one’s freedom was a vulnerable position. One’s freedom papers could be torn up at any time and be sold back into slavery.

Ultimately, Grandy was able to purchase his second wife for $300, his son for $450, and discovered that six of his other children had been sold in New Orleans. Of these, two of his daughters, Catherine and Charlotte, bought their own freedom.

The details of Grandy’s life come from his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Moses Grandy; Late a Slave in the United States of America, which was dictated to George Thompson, a British abolitionist in 1843. Narratives such as Grandy’s were powerful tools that gave first person accounts of the harsh realities of slavery. This publication allowed Grandy to raise additional money to free his family.

Today, a thoroughfare in Chesapeake has been deemed Moses Grandy Trail to mark not only his notable contribution to building the Great Dismal Swamp Canal and his superior skill in navigating boats, but perhaps more importantly, to denote his unyielding determination to live as a free man.

No Comments