Article and photography by Joshua Fitzwater

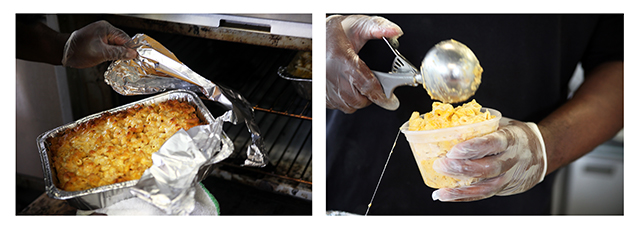

Lead photo: Macaroni & cheese by Emmanuel “Scootie” Logan at The Original Ronnie’s BBQ in Varina, Virginia

Ten miles south of Richmond’s bustling Shockoe Bottom, along the well traveled sun soaked Virginia Capital Trail, some of the best macaroni and cheese the state of Virginia has to offer can be found. In Varina, at the intersection of New Market and Varina Roads, the rich smell of wood, fire and billowing smoked meats tickle the noses of drivers who breeze through the green light. Those caught at a red, the lucky ones, get to soak in the meat perfume for a minute or two before the light changes. Often, non-locals make a u-turn to investigate.

Above: The Original Ronnie’s BBQ restaurant in Varina, Virginia

Regulars of Original Ronnie’s BBQ, however, are a different story. While they know that outstanding ‘cue set to the soundtrack of r&b and soul pumping from standing speakers beside the hot smokers outside are available Friday through Sunday, they quite often choose to stop in on Sundays. The only day of the week Emmanuel “Scootie” Logan makes his prized macaroni and cheese.

Above: Emmanuel “Scootie” Logan making his prized macaroni & cheese

Scootie, owner Ronnie Logan’s nephew, is a caterer by trade. His macaroni and cheese, consists of a multitude of different cheeses, condensed milk, a closely held to his large barreled chest spice blend and other unmentionables, and his macaroni and cheese recipe is best understood through a soul food lens. As food writer and podcaster Debra Freeman explains, “soul food is a term that attempts to capture historical African-American foodways. The term soul food came about in the 1960’s, first used in print in 1964 to reclaim Black identity as it pertains to food in America. While Southern food encapsulates everyone that lives in the South, soul food specifically refers to Black cooking and recipes.”

Above: “Scootie” Logan loading his macaroni and cheese into a backing pan

In regards to important characteristics of soul food macaroni and cheese, Freeman further explains, “the key component to making soul food macaroni and cheese is that it is baked, seasoned very well and typically does not include breadcrumbs. Mac and cheese is held in high esteem at family and community gatherings, and not just anyone can bring it. If you have been asked to make the macaroni and cheese then you are held in high esteem.”

Above: “Scootie” Logan baking and serving his prized mac & cheese

In terms of family and community in Varina, the Logan’s food is central to both. Scootie’s macaroni and cheese is a passed down family recipe that he has adapted as his own and his Uncle Ronnie, who often can be found rubbing elbows with curious customers enticed by the alluring smell of his barbecue, likes to share a bit about his family history. In particular, Ronnie talks about how for years members of his family owned and operated a market within eyesight from where his barbecue joint stands today, and that it once served the community in generations past. Ronnie also took part in community whole hog pit-dug Virginia barbecue cooks in Varina.

Above: Emmanuel “Scootie” Logan with a fresh tray of his macaroni & cheese

As far back as the Logan’s family food ties branch out within their community in Varina, Virginia, it is merely a single branch amongst the deep historic culinary roots Virginian food and macaroni and cheese in America share. Close to two centuries before the term soul food was coined to proclaim a Black identity within American food, James Hemings, an enslaved Virginian man, ironically enough, who was not allowed the freedom of an autonomous identity, would nonetheless be the first person to popularize macaroni and cheese in the country. The assertion of Hemings as the first to popularize macaroni and cheese in America and, more specifically, his role in introducing the dish to the country, however, is highly contested in scholarly circles.

Enslaved by Thomas Jefferson, Hemings, the first chef de cuisine of America, was brought to Paris, France and began his French culinary training in 1785. Once there, along with other French culinary standard dishes of the time, he picked up France’s appropriated macaroni and cheese, a version with white sauce or cream and Gruyère cheese, therefore much creamer than the oldest known Roman-Italian macaroni dishes as food historians Adrian Miller and Karima Moyer-Nocchi detailed in a recent article for Epicurious.

According to Miller, “it is important and more sound to say that Hemings may have contributed to the popularization of macaroni and cheese in America versus being the introducer of it.” Miller points to misleading American ads of the 1940’s depicting Jefferson who historically was very fond of the dish, serving it to other founding fathers of America and how that gave a distorted picture of the origins of macaroni and cheese in America. As he further explained, “before Hemings returned to America from France in 1789 where likely he would serve it to Jefferson both in Philadelphia and Monticello, recipes for macaroni and cheese were already in circulation in Virginia and some of the other colonies.”

Miller and Moyer-Nocchi point to pasta recipes in English cookbooks from 1710-1747, some of which were on the home shelves of George Washington and Ben Franklin, and were in circulation in some of the colonies, so as to show the use of pasta in America before Hemings’ return from France. Further, as Miller and Moyer-Nocchi argue, “[…] it was in Elizabeth Raffald’s The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769), another cookbook that circulated in the colonies [before Hemings return], where we get our first proper recipe for macaroni and cheese in English. Her recipe calls for thickening the sauce with butter rolled in flour, denoting once again a predilection for creaminess.”

While Miller and Moyer-Nocchi are right to point out that those dates do in fact predate when Hemings brought his French trained version of macaroni and cheese back to America, to fully consider Hemings broad influence on American macaroni and cheese, one must contend with the reach and influence of 1824’s The Virginia Housewife cookbook. In terms of cookbooks in America, one can not understate its impact. As Fredericksburg based author and Virginia food historian, Joseph R. Haynes details concerning The Virginia Housewife, “the book was first published in 1824 and it was republished at least nineteen times before the outbreak of the Civil War. I [Haynes] have found recipes in parts of the South that are direct copies of recipes in that book. All over the South many women in the 1800s cooked or had their enslaved cooks prepare foods using it as a guide.”

As Freeman also explains, “it is [widely] considered as the most influential cookbook in 19th century America.” One example Freeman points to is culinary historian Karen Hess’s words regarding the book, “ […] nothing in the history of early American cookbooks quite prepares us for the sumptuous cuisine presented.”

The Virginia Housewife cookbook, authored by Jefferson’s cousin, Mary Randolph, was far more influential and widespread than Raffald’s Experienced English Housekeeper. Further, Freeman argues that, “several secondary sources support the assertion that Randolph used many of Hemings’ recipes, and it is not a leap in logic to connect the historical dots and arrive at that conclusion. Many recipes and ingredients, such as okra and gumbo, which were traditionally prepared by African-Americans at the time, are listed throughout the book.” Freeman also points to historian Mary Tolford Wilson’s words which describe the choice in ingredients as “‘peaceful integration’–the adoption of slaves’ food by the slave-owning class.”

Freeman is quick to point out that Randolph and Hemings were likely also in close proximity during different periods of their lives to further substantiate the argument that Hemings’ recipes and work ended up in The Virginia Housewife. As Freeman explains, “Randolph’s brother, Thomas Randolph Mann, is Jefferson’s son-in-law, and historical evidence supports that the families spent significant time together in Charlottesville.”

Freeman also notes that it is important to consider, “after the death of Jefferson’s wife, Randolph became the hostess of his house. As she was being served the half-Virginian and half-French meals on a daily basis, Randolph had first hand knowledge and proximity to Hemings’ food, and once she became mistress of Monticello it would not have been difficult to note the recipes used. Hemings would have certainly been aware of what food the slaves on Mulberry Row were preparing as well as what went into those meals. Perhaps most obviously, it would be a stretch to imagine someone of Randolph’s stature would cook in a kitchen alongside slaves who were churning out meals in front of roaring fires for 12 hours a day or more.”

Paralleling this method of reasoning but with The Virginia Housewife omitted, in Miller and Moyer-Nocchi’s Epicurious article, when considering how macaroni and cheese was made American, they state, “over the course of the [19th] century, the macaroni and cheese dish underwent a cultural transition, traceable in the numerous cookbooks published in England and the US.”

They further go on to state, “The 1800s were a golden age for white American women cookbook writers, as the domestic arts was one of the few domains in which they were permitted to flourish unimpeded, and nearly all of these cookbooks contained recipes for macaroni and cheese. Yet, it was enslaved Black women who were in the kitchens, hands-on, either perfecting the recipes that would end up on the printed page, or translating heirloom recipes into reality, in one way or another passing on their craft to the next generation of cooks.”

Miller and Moyer-Nocchi’s assertion here seems quite plausible. One must ask however, if this reasoning is given to the culinary contributions of enslaved Black women of the time, that they were “translating heirloom recipes into reality”, and that “the perpetuation of macaroni and cheese became the legacy of Black women cooks”, why do Miller and Moyer-Nocchi not afford this same type of reasoning to Hemings?

Instead, they write, “His [Hemings] case merits further investigation into the tribulations of skilled, educated formerly enslaved peoples’ attempting to assimilate into a society mired in cultural stigma. But as for macaroni and cheese, there is no corroborating evidence of Hemings as ambassador.”

Considering the arguments for Hemings’ recipes likely being included in The Virginia Housewife, that Hemings and Randolph were in proximity to each other during different parts of their lives, and the popularity of The Virginia Housewife superseding the popularity of other cookbooks in circulation in the colonies in the 1880’s, including The Carolina Housewife of 1847, which Miller and Moyer-Nocchi cite, and which is published twenty three years later, then one must concede that Hemings is in fact the first ambassador for American macaroni and cheese. The only way not to concede this point would require a higher burden of truth for Hemings’ influence than that of enslaved Black women of the 1800s.

——————————————————————————————————–

Select back issues of Southern Grit Magazine available to order at southerngritmagazine.bigcartel.com

——————————————————————————————————–

What proves to be even more important than leveling the burden of proof when considering Hemings as ambassador for American macaroni and cheese, however, is to look at the specific descriptions of the recipes Miller and Moyer-Nocchi cite in their article that were available in the colonies, and predate the release of The Virginia Housewife’s macaroni and cheese recipe.

While Patrick Lamb’s Royal Cookery of 1710, Edward Kidder’s the Receipts of Pastry and Cookery, written in 1720, and The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, written by Hannah Glasse in 1747 all come before The Virginia Housewife, Miller and Moyer-Nocchi themselves concede that the recipes inside them are not macaroni and cheese recipes, but rather recipes that involve pasta and demonstrate that, “pasta was not unknown among the Yankee Doodles”. Miller and Moyer-Nocchi however, as mentioned earlier, point to Elizabeth Raffald’s 1769 cookbook, The Experienced English Housekeeper, as providing the colonies with the “first proper recipe for macaroni and cheese in English.” At first glance, when looking at Raffald’s recipe, which reads, “Boil four ounces of macaroni till it be quite tender and lay it on a sieve to drain. Then put it in a tossing pan with about a gill [a quarter of a pint] of good cream, a lump of butter rolled in flour, boil it five minutes. Pour it on a plate, lay all over it parmesan cheese toasted. Send it to the table on a water plate, for it soon gets cold”, one might reason that this recipe indicates “proper” macaroni and cheese finding its way around kitchens in the colonies before Hemings’ influence, but close inspection of Raffald’s recipe is paramount before making that conclusion.

In Raffald’s recipe, the macaroni and cheese is not baked. This is important on several levels and requires deeper inspection. First, one must recognize that the English versions of macaroni and cheese were both based on and came after the French version of macaroni and cheese which is the style Hemings learned and brought back to America. Second, Miller and Moyer-Nocchi fail in their article to cite a single cookbook or recipe for macaroni and cheese in America that predates The Virginia Housewife that includes the combination of the creamier, “white sauce or cream and Gruyère cheese” French approach paired with the act of baking. Despite that, Miller and Moyer-Nocchi state the following about what substantiates American macaroni and cheese.

“You’re making up a macaroni and cheese casserole for the neighborhood potluck. As you stir, the plump elbows surrender to the thick, creamy orange cheese sauce. The voluptuous, squishy sound of walking barefoot through mud promises success. A top layer of grated cheese, browned to a golden crust, will add the final irresistible allure to this quintessentially American dish. But how did a combination of cheese and pasta—two European cultural exports—become one of America’s best-known staples?”

Sometimes the devil is in the details and there is an important distinction here that Miller and Moyer-Nocchi are overlooking. While Raffald’s, The Experienced English Housekeeper macaroni and cheese recipe that they herald calls for, “lay[ing] all over it parmesan cheese toasted” which at first glance might seem like an act that provides Miller and Moyer-Nocchi with, “the final irresistible allure” to American macaroni and cheese, in fact, separately toasted parmesan sprinkled on top of unbaked pasta and also unbaked melted cheese and cream is quite removed from the experience of today’s potluck casserole macaroni and cheese. That experience, which includes the true browned golden crust so synonymous with proper American macaroni and cheese is only achieved by the integration of the pasta, white sauce or cream and a creamier cheese all baked together to create the real golden brown crust that is so quintessential.

This oversight illustrates the greatest shortcoming in Miller and Moyer-Nocchi’s conclusion that Hemings was not the ambassador for American macaroni and cheese. If a browned golden crust, again not achieved by simply sprinkling toasted parmesan on top, adds, “the final irresistible allure to this quintessentially American dish”, then, the combination of cheese and pasta, are not the only two components in a recipe that make up proper American macaroni and cheese. Raffald’s recipe does not have the real “final irresistible allure” component Miller and Moyer-Nocchi speak of in today’s American macaroni and cheese but The Virginia Housewife in fact does, as it calls for the dish to be baked as detailed below.

Boil as much macaroni as will fill your dish, in milk and water till quite tender, drain it on a sieve, sprinkle a little salt over it, put a layer in your dish, then cheese and butter as in your polenta, and bake it in the same manner.

With that in mind, simply put, proper American macaroni and cheese at a minimum must include four key components, cheese, milk or cream, pasta and baking. Boiling the pasta is a fifth but as the French, English and American recipes all call for that, it’s not included in terms of minimum requirements along with all other universally held variables. One must conclude that Hemings is at the very least the ambassador for American macaroni and cheese, as he was the first to introduce the French recipe precedent, which supersedes the later English recipe that is void of baking. Or Hemings could, in actuality, be the creator of what should be called American-style macaroni and cheese, unless the historic French macaroni and cheese recipe pre-Hemings return from France includes baking. Showing an English recipe for macaroni and cheese pre-Hemings which includes baking would also change the strength of this argument put forth. In Miller and Moyer Nocchi’s article, neither are presented.

The distinguishing factor, baking, could also prove to disrupt the currently accepted understanding of what today is accepted as the inception of soul food style macaroni and cheese, which also is known under the monikers of Southern or casserole macaroni and cheese, not to be confused with stove top, instant or Kraft macaroni and cheese. Upon further research, one could potentially draw a direct line back in terms of cooking application from ‘60s soul food macaroni and cheese to Hemings, be it in his presentation of the proper French version or the invention of his new American-style, again depending on the component of baking in French recipes. Consequently, stove top style macaroni and cheese, void of baking and only boiled, may in fact hearken back to English style macaroni and cheese recipes introduced to the colonies.

Putting the specifics aside of how the baking component plays out amidst more historical recipe research, James Hemings, a Virginian, born in Charles City County and America’s first Chef de Cuisine, should be seen as our nation’s ambassador for macaroni and cheese. From bringing the knowledge of the dish back from France in its proper form, to likely cooking it in multiple states, and through logical deductions and research shown to have at the very least played a part in the recipe listed in The Virginia Housewife, Hemings is positioned as the central player in the American macaroni and cheese story. It’s a story whose legacy today is told deliciously well by the likes of “Scootie” Logan in Varina, Virginia and other talented chefs, cooks, and caterers across our country.

Above: Emmanuel “Scootie” Logan at The Original Ronnie’s BBQ

For more on Emmanuel “Scootie” Logan and Ronnie’s BBQ, visit @creationsbyelo and The Original Ronnie’s BBQ

To read Miller and Moyer-Nocchi’s article in Epicurious on macaroni and cheese, visit HERE

To read Freeman’s article on James Hemings, visit HERE

No Comments