Article by Robert Linné

Photography by David Flores

Takeout from D’Annunzio’s Bakery

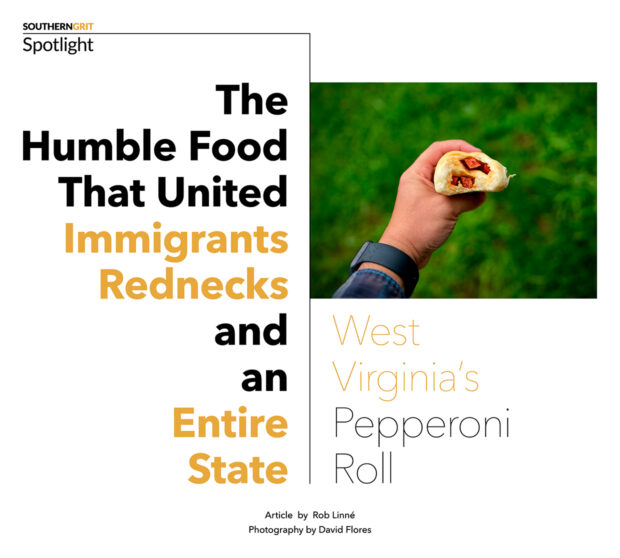

My first taste of West Virginia was almost heaven – a small loaf of a slightly sweet American-style yeast dough wrapped around a very generous knob of ground pepperoni, baked until beautifully browned. The sausage had given up a good amount of spicy grease to the spongy dough at the center, while some leaked out in the bake to make for crunchy bites at the corners of the crust. The ratio of pepperoni to roll seemed a little wrong—almost sinful—but like all the best transgressions this first bite led to another and then another.

This West Virginia classic, the pepperoni roll, is almost impossible to resist as I found during my travels through the state. I also found that there is a lot of the transgressive wrapped up in its long history.

I was in the Mountain State to give a talk at the centennial commemoration of the Blair Mountain miners uprising, but I was also down for sampling the state food with a fascinating story resonant of Appalachian labor history. A simple hand-held meal that was declared to be the official state food by the West Virginia House of Representatives at the end of their Spring 2021 session, the roll is ubiquitous across much of the state. I had no difficulty finding them. Old school Italian bakeries offer shelves stacked with warm-out-of-the-oven bakes, but grocery stores, burger stands, baseball stadiums, gas stations, and donut shops also offer their own versions.

Sweet Nana’s donut shop in Clarksburg was an excellent introduction to this singular bite of Appalachian foodways. I had read up some on the history of the treat, but the ground pepperoni, the sweet dough, the donut shop vibe, indeed the entire experience sparked more wonder and questions.

The nice young worker behind the counter could only chat a minute before getting caught up with phone orders. However, the bored threesome of teens hanging about did eagerly jump into conversation with me. Each pointed me towards their favorite bakery or deli rolls in town, but their hearts seemed to belong to those I could not access, the homey stuffed breads their lunch ladies made at school or the ones made by parents sold as fundraisers at basketball games.

I asked if they were a meal or a snack and they stared quizzically at me before listing the many ways and times of day you can have pepperoni rolls. They can be eaten for a school lunch, dinner at a football game, a re-heated breakfast, an afterschool snack, late night after going out with friends, or as on this day—a skipping school snack. (These young scholars declined to give permission to name them in my article because I gave them a bit of a hard time about skipping). The boy of this cohort noted he can tell which neighborhood a family comes from by which bakery box appears at birthday parties, and they all told me they expect the fancier, mini versions at bigger affairs like weddings or funerals.

The teens knew a lot about the different varieties and where they can be had, but when asked if they knew the history of how their favorite fast food came about, they shrugged and suggested they’ve always just been a thing here.

The story behind the pepperoni roll is fascinating but the lack of historical memory, even in the region of their birth, is probably the norm. Chris Williamson, a born-and-raised West Virginian friend, remembers his mom buying them for him and his sister at the grocery deli when they were little, but it wasn’t until he was a college student at West Virginia University that he learned about them on a deeper level and a life-long love was sparked.

“When I was a broke college student, I would often buy two pepperoni rolls and a Diet Coke from the Mountainlair—the University Student Union— because, at the time, it only cost me three dollars. Pepperoni rolls were also common at football tailgates and basketball games and a regular late night snack for students.”

Not until he returned to Morgantown for law school, set on becoming a labor lawyer, did he fully make the connection between the food he loves and the rich labor history of the state he loves.

“Italian immigrants moved to all parts of West Virginia to work in the mines, and they took loaves of bread and sticks of pepperoni with them to eat as a hearty meal while they were underground. The largest concentration of the Italian miners was in north central West Virginia, around Clarksburg, Fairmont, and Morgantown. Residents in that area still celebrate their Italian heritage, including at the annual West Virginia Italian Heritage Festival in Clarksburg,” said Williamson. Sometime in the early 1920’s the Italian bakeries started baking substantial sticks of pepperoni right into the bread and an Italian-American classic was born.

Storefront of D’Annunzio’s Bakery in Clarksburg, West Virginia

Like so many of our American regional foods developed for workers’ meals away from home, the pepperoni roll had to be uncomplicated, portable, filling, and delicious. After trying the very traditional rolls at old school D’Annunzios Bakery, which has been baking bread since the 1920’s, I can attest that the rolls are both super delicious and calorie dense. I could see how the roll would work for the miners back in the day and later for their grandkids, like Williamson, who could rely on them to make it through the college years and even law school. Drawing that line from the hardscrabble but determined lives of their grandparents to today’s generation can make the food even more special. When I asked around, people who knew the history told me that the pepperoni rolls are still here in part to remind people of the life their ancestors lived, but also how they made things beautiful and heartwarming, even in tough times.

I witnessed first-hand how much the pepperoni roll has become woven into contemporary culture of the state when I stopped by Books and Brews pub in the gentrifying Elk City District of Charleston. The lofty space with pressed tin ceilings and books lining the walls was buzzing with families geared up in Mountaineer blue and gold to watch the opening day game. A majority of tables had an order of their award-winning pepperoni rolls (People’s Choice Award: Best Dish Charleston). Their rolls are more involved than the traditional versions in Clarksburg, but it would be difficult to argue against the enhancements. The well-proofed dough was stuffed with mozzarella as well as pepperoni and served with a side of pesto made of ramps, the wild green onions beloved in Appalachian kitchens. These citified rolls were great with a few local craft beers, but I will always remember their pesto as the best I have ever had.

Storefront of Tomaro’s Bakery in Clarksburg, West Virginia

The tastiest pepperoni roll I sampled came out of the V-Mart gas station in Comfort, West Virginia, a tiny hamlet lining a winding mountain two-lane in Boone County. These masterpieces were oozing browned provolone and spicy pepperoni grease, but what made them remarkable was the light, crackly outer crust dusted with parmesan. I asked who made them, and the lady behind the register called for Haley (Ceravolo) to come from out back to talk with me, but not before warning: “Don’t give away any secrets!”

When I asked why they were so good Haley laughed and whispered, “it’s the grease.”

“No really,” she went on, “I think ours are not as doughy as others. People love the pepperoni with cheese, especially later at night.” When I asked if she made a lot of them, she told me, “yes, we have to have them coming out for customers day and night.”

From Comfort I drove about 45 more minutes through breathtakingly beautiful mountains to get to my final destination, Matewan, West Virginia. And this is where I think the story behind the pepperoni roll gets more interesting. Walking the town where one of our nation’s darkest days played out, the line connecting a beloved comfort food with the day-to-day survival of people who helped build our country became impossible to ignore.

Perhaps you remember the classic 1987 John Sayles film, Matewan, which shocked a lot of viewers at the time by clueing us into the story of state law enforcement and the U.S. military siding with coal bosses and firing upon American citizens (including many World War I vets) who were striking for a decent standard of living. The number killed is unclear, but at least 100 lives were lost, and the survivors were devastated.

The way the film sympathetically portrayed the people brutalized by an inhumane system opened my eyes and changed my focus as a teacher forever. Across my decades as an educator, I have experienced some of the most enlightening moments with students when working with them to uncover the working-class histories of their families and local communities.

——————————————————————————————————–

Select back issues of Southern Grit Magazine are available at southerngritmagazine.bigcartel.com

——————————————————————————————————–

This work is what brought me to West Virginia to speak at Blair100, and my eyes were once again opened to the power (and the necessity) of uncovering hidden histories of the people. Many local folks who spoke at the various commemoration events lamented that even though they grew up in coal country, and had direct relatives who worked in the industry, the stories of their violently oppressed ancestors bravely rising up had effectively been buried by official narratives told in schools and museums. Labor scholar Charles Keeney told us at the commemoration that even though his great grandfather Frank Keeney was a famous organizer for the miners, his family had learned it was safer to keep that story quiet, and he did not learn of this pivotal family history until he poked around with his own questions. All of the speakers reminded us that a concerted effort is needed to keep working people’s stories alive.

For example, activists and educators are now working hard to reclaim the red bandana and the entire notion of redneck. Too many Southerners (as well as outsiders) misread “redneck-ness” as essentially reactionary. Along with loving college football and fishing, a redneck is just supposed to be anti-immigrant, anti-union, and anti-woke. It just has always been that way, part and parcel of our history.

Except a deeper dive into history tells a far different story. When poor white Appalachians, African-Americans, and recent immigrants from Italy and Poland came together and wore red bandanas tied around their necks as a sign of solidarity, women fought alongside men. Moneyed interests knew this kind of solidarity represented a major threat that needed to be divided and destroyed. The state sided with capitalism and put down the uprising with a brutal show of force. As Don Chafin, Sheriff of Logan County, flippantly commanded, “Kill all the rednecks you can!”

By reclaiming the red bandana and the radical redneck identity folks are trying to get a new generation to embrace the best parts of our heritage, rather than the most odious, and realize that history in our storied regions is never dead. We have only ever made progress in the South, and the U.S., when working people have rejected the calls to hate other working people and stood in solidarity for better lives for all our children. Such a reclamation project can be effective. The inspiring, successful against-all-odds, and nationally influential West Virginia teachers strike of 2018 represented a return to working-class militancy and solidarity in the state. Many of the teachers began wearing the red bandana and sharing stories of the state’s labor history to inspire and hold the line.

That history can be lived through and learned from via many aspects of our culture, including music, food, and art. Food is best when it is delicious and comforting, but also tells a story. Many of our most loved regional foods tell great stories, including labor and working-class history.

The New Orleans po’boy originated during the 1929 Streetcar Drivers Strike when a local coffee stand stood in solidarity with the workers by passing out sandwiches to feed the picketers. The first iterations of the Hawaiian lunch plate were bento boxes filled with rice and various leftovers plantation workers brought into the fields with them. The plates, now a fusion of different cultures that were brought in to work the fields as well as break strikes, tell the story of workers who were violently oppressed and lost unionizing battle after battle until the Japanese, Filipino, and Chinese immigrants managed to come together in a coalition that could fight the divisive tactics of the owners.

Let’s learn these stories of our working-class foodways and tell them to the next generations. I want to start traditions like Chris Williamson shared this past Labor Day. He posted photos on social media of his kids in red bandanas eating the pepper rolls he and his wife made from scratch. The caption read, “Remembering the early Italian American West Virginia coal miners as we eat pepperoni rolls this Labor Day weekend.”

Robert Linné is a professor of education at Adelphi University. His writing focuses on labor and working-class history and cultures. He also serves on the Board of Directors of the Remember the Triangle Factory Fire Coalition.

1 Comment

Dr. Linne has constantly exhibited a penchant for weaving interesting pieces of the American fabric into his immigrant labor histories. It helps us remember that their struggles should remain above the false narrative promulgated by certain factions of historians. Bravo, Rob