Article by Fitz

Photography by Fitz and Matt Wade

It is 2:45 a.m. on March 13, 2021 and I am driving to Woodstock, Virginia from Richmond for a barbecue. Normally this would be a relatively common occurrence, after all, I publish a food magazine. These days however, my life is anything but normal.

Starting in December 2020 my stomach stopped working. Two weeks later my heart began skipping and dropping into my stomach. Sweats, sleepless nights, continuous irregular heartbeats and thousands of dollars accumulated from ER visits and heart and stomach specialists. All, by the way, amidst the earlier days of the U.S. beginning to reckon with the coronavirus and the hospitals in Richmond pushed to capacity.

So why am I driving in heavy fog in the dark on no sleep to film a barbecue? The answer, like Virginia barbecue itself, is complex. But bear with me, I’ll try to keep this as short as possible.

1752 Barbecue Pitmaster Justin Wightman salting hogs

First, let me say that I’ve noticed something in popular society in recent years and I think some of you have as well. Men are under attack. More precisely, masculinity is under siege. Even by saying that, I will likely be attacked. Don’t believe me? Just briefly, take a survey of popular entertainment and films to illustrate my claim. Here is a brief rundown of popular fictional male characters and their recent fates dictated by today’s storytelling.

1752 Barbecue Assistant Andrew Case building the barbecue pit

Let us begin with a look at the recent Star Wars sequels. Han Solo, in the late 70’s and 80’s, was the personification of cool masculine, can-do assuredness. However, he’s stabbed unceremoniously and thrown to his death down a dark pit in Episode VII The Force Awakens.

His son, Ben Solo, a.k.a. Kylo Ren, a.k.a. the perpetrator, is insufferable and ruled by his impulses throughout the sequels. This is important because essentially Kylo Ren is playing the modern day equivalent of head villain Darth Vader but without the strength, cunningness or determination of his idol and classic male antagonist from Episodes IV, V, VI. Also, let’s not forget that juxtaposed with Han Solo being stamped out without thought or care, his lover and Kylo Ren’s mother, feminine icon Princess Leia, while under attack, gets thrown through thick reinforced glass out into the vacuum of space in Episode VIII The Last Jedi and using only her will, glides back to safety with minimal damage. Luke Skywalker, the ultimate optimistic and heroic male is even reimagined as cynical and an unsure recluse. And in Episode VIII, he has a mental breakdown and tries to kill a young Ben Solo, essentially setting much of this Kylo Ren villainy and madness into motion in the first place.

1752 Barbecue Pitmaster Justin Wightman putting the hogs on the pit

How about we move to Marvel. Star-Lord of Guardians of the Galaxy, a throwback to male coolness of the past, loses his cool and foils the elimination of Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War during The Battle of Titan when Thanos is pinned down and vulnerable. Again, driven by an inability to control his emotions, Star Lord’s blunder will seal the elimination of half of the universe’s population. Oh, and even after the horror of Thanos’s finger snap of death is reversed in Avengers: End Game, Iron Man is dead, Captain America is geriatric, Thor is fat and a cheeseburger away from a heart attack, Hulk’s a cripple, and so on. The Marvel Cinematic Universe is devoid of any male role models that have their proverbial shit together.

Salted hogs placed on the pit for a Virginia barbecue cook by 1752 Barbecue in the Shenandoah Valley

Still not convinced? Let’s talk Terminator. Is John Connor still the hero of the resistance against Sky Net? No, not anymore. In Terminator: Dark Fate, he is stamped out young and unceremoniously much like Han, as mentioned before. Hell, even the Terminator, Mr. Olympia himself, Arnold Schwarzenegger, is hiding in a cabin cuckolded by his wife and on the sidelines.

Let’s move it away from fiction. Let’s take a look at men active in popular culture who are respected by many men in society and take a quick survey of the happenings in recent years. Dave Chappelle essentially can’t tell jokes anymore and is a step away from being canceled. Kevin Hart is being held to task for a joke from a decade ago and for all intents and purposes was forced to step down as host of the Academy Awards. Joe Rogan is categorized on CNN as an idiot and taken to task for supposedly taking a pill for animals upon contracting coronavirus despite being prescribed it by a doctor and it being in use for humans for years. And let’s not forget about Jordan Peterson, a Canadian professor, philosopher and self-help author. He’s vilified and portrayed as a nazi in Marvel Comics. His sin? He refuses to be mandated by his government to use a pronoun.

——————————————————————————————————–

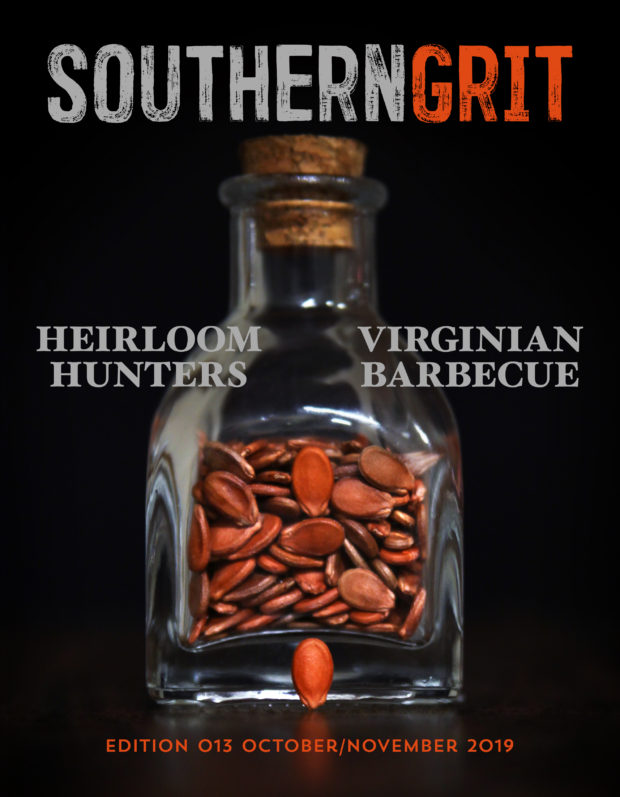

Select back issues of Southern Grit Magazine are available for purchase in limited numbers at the following link southerngritmagazine.bigcartel.com

——————————————————————————————————–

Now all that said, I’m sure I’m bound to hear NO, these cases involve sexism or racism or colonialism. Well, I’ll have to debate those particulars with you another time, right now I need to get back to barbecue.

Long set up short, I run Southern Grit, so I’m going to highlight real men when it moves me. Just as I write about women, people of color and those with different sexual orientations who make a difference in their field, community, and particularly in barbecue. After all, barbecue as we know it today began in Virginia and Justin Wightman and Craig George of 1752 barbecue in Woodstock are doing the most authentic interpretation in the state today. And, in a nutshell, that’s why on zero sleep and with only a handful of pills keeping my heart rhythm from complete ruin, I went to visit with them as they cooked whole hogs the Virginia way.

1752 assistant Andrew Case making wood fired coals for the pit

Virginia barbecue was not born in a restaurant tradition. It was born in a community and political tradition. This is important because in many ways Wightman and George have made their mark on barbecue with large whole hog cooks for their community every year at the annual Shenandoah Valley Autumn Fest. The same way sponsored political candidate signs provide the backdrop for their large cooks each year at Autumn Fest, one can draw a direct correlation to early Virginia barbecues where George Washington wrote that he attended and were often held to likely elicit political sway.

With some modern advancement, iron rebar instead of sticks to hold up the hogs over the pit, a chainsaw next to the salting tables to cut down the wood for making coals versus axes, when I pull up to the cook site right off the Shenandoah river where Wightman and George are prepping two 140 plus pound hogs, I immediately spot the flapping Virginia flag dimly lit by burning feeder fire. Other than author Joe Haynes (Virginia Barbecue: A History), a friend of Wightman and George, one is hard pressed to find a Virginia pitmaster more versed in the history of barbecue than these two. After hellos and other formal greetings were exchanged, Wightman and I began to discuss the immense effort that enslaved pitmasters must have given to pull off these types of cooks in the past. American barbecue was born in the hands of early colonial enslaved Africans and soon thereafter African-American Virginian pitmasters. To best understand it’s formation, I like to invoke Haynes’ words that, “Southern barbecue is a creolization of African-American, Indigenous, and European cooking in Virginia.” It’s the melding of the European trench with the indigenous hurdle to create the original barbecue pit, along with the African-American pitmaster front and center helming the cook and using European vinegar and African red pepper to baste over the direct heat of wood fired coals.

Making the vinegar based baste

After salting the hogs, Wightman, George and their assistant Andrew Case shovel wood fired coals into strategic parts of the pit. The placement of the coals is calculated as the pigs first go on the pit with the distribution of the coals being the most bountiful under the hams and other areas requiring higher heat to cook. The process of making coals in the feeder fire followed by distributing them under the hogs continues until a much needed lunch brings relief from occasional shin and forearm burns.

Lunch is cooked over an open fire as well, mere feet away from the pit. Local sausage and eggs along with scrapple sizzle in cast-iron pans over a grate hot from the same feeder fire of wood coals. As I’m eating this meal, which rivals some of the best I’ve had in six years of covering restaurants in my magazine, I compliment George on the first barbecue I saw them do, the more than twenty-four hour, six whole hog cook for the 2019 Shenandoah Autumn Fest. By the time the four of us finish remembering that cook, our plates are clean and the early morning sun has given way to the high and bright noon sun.

———————————————————————————————————–

Drawing on hundreds of historical and contemporary sources, author, barbecue judge and award-winning barbecue cook Joseph R. Haynes documents the delectable history of barbecue in the Old Dominion. Virginia Barbecue: A History is on sale now at Amazon HERE and Barnes & Noble HERE

———————————————————————————————————–

George and Case continue to take turns feeding the pit with coals as Wightman takes his chainsaw to the forest’s edge to replenish the wood pile. The speed, strength and efficiency these men mold fire to their will and shape wood to their liking conjures up similar feelings I get when watching the likes of hunter Steven Rinella track and take down a buck. It’s an act that showcases knowledge that only comes with years of experience. After the wood is handed to Case for splitting, Wightman hunts down the perfect long thin tree branch to shape into a Virginia basting wand. It’s at that moment that an unnerving PVC (premature ventricular contraction) thud in my chest reminds me that it has been four hours since my last heart pill.

The Virginia wand, essentially a tree limb with a cloth or rag connected to its end, is a precursor to the basting mop in use today by Southern Pitmasters. Pictures from the mid-to-late nineteenth century of Black Virginian pitmasters like Juba Garth holding and using these wands at Virginian barbecues have survived. It also can’t be overstated how important the right time to baste these hogs and flip them is in protecting the skin and meat from burning. Early African-American Virginian pitmasters did it by look and feel, and they were culinary craftsmen of the highest order.

1752 Pitmaster Craig George basting the hogs

As the sun starts to drop a bit from the height of the sky and squints shape the faces of Wightman, George, Case and I, it is time to flip the hogs. Due to years of practice, flipping these 140-plus pound hogs is but a formality. After another modern convenience, an instant-read thermometer is used to check the temperature of the hogs, Wightman and George make quick work of the flip. Only a quick redistribution of wood fired coals remains before George begins to baste.

Visually, the moment could not be better for basting. The sun is just low enough now to stream through the trees and smoke and hit George with a pleasant contrast worthy of a great Virginian pitmaster paying homage to the great pitmasters of the past. And while it is a grave misfortune that these pitmasters before emancipation didn’t have a choice to cook or not, they nonetheless did it with great precision that deserves to be recognized.

Taking the temperature of the hog, saucing the barbecue, and the finished minced barbecue

After more basting and a few more hours of the pigs cooking on their backsides, the sun is not far from setting. Again, a testament to Wightman and George’s proficiency, I watch as they pull the large finished hogs off the pit, break them down, and slice and mince them. In Virginia, whole hog, as Haynes explains, is served either sliced or minced, not pulled or chopped as it’s known in Carolina.

At sunset, I take another heart pill. Maybe it’s an hour or so early before my next dose is due but I don’t want to take any chances. After all, I’ve got a three plus hour drive ahead of me to get home. Since these health issues began, I’ve found myself doubting the way I spend some of my time. Do I really need to watch two hours of Netflix? Shouldn’t I go visit my aging dad instead? Things like that. But as I say my goodbye to George and Wightman, I don’t have those concerns.

1752 Pitmasters Craig George (Left) and Justin Wightman (Right) with Southern Grit Magazine Editor, Fitz (Center)

I’m a Virginian. With a couple of pounds of barbecue in tow, I’m bringing a taste of Virginian history back to my partner and her daughter. If I hurry, this can be my family’s dinner tonight. I can’t think of a more meaningful way to spend my time.

For more on 1752 Barbecue, visit facebook.com/1752Barbecue

No Comments